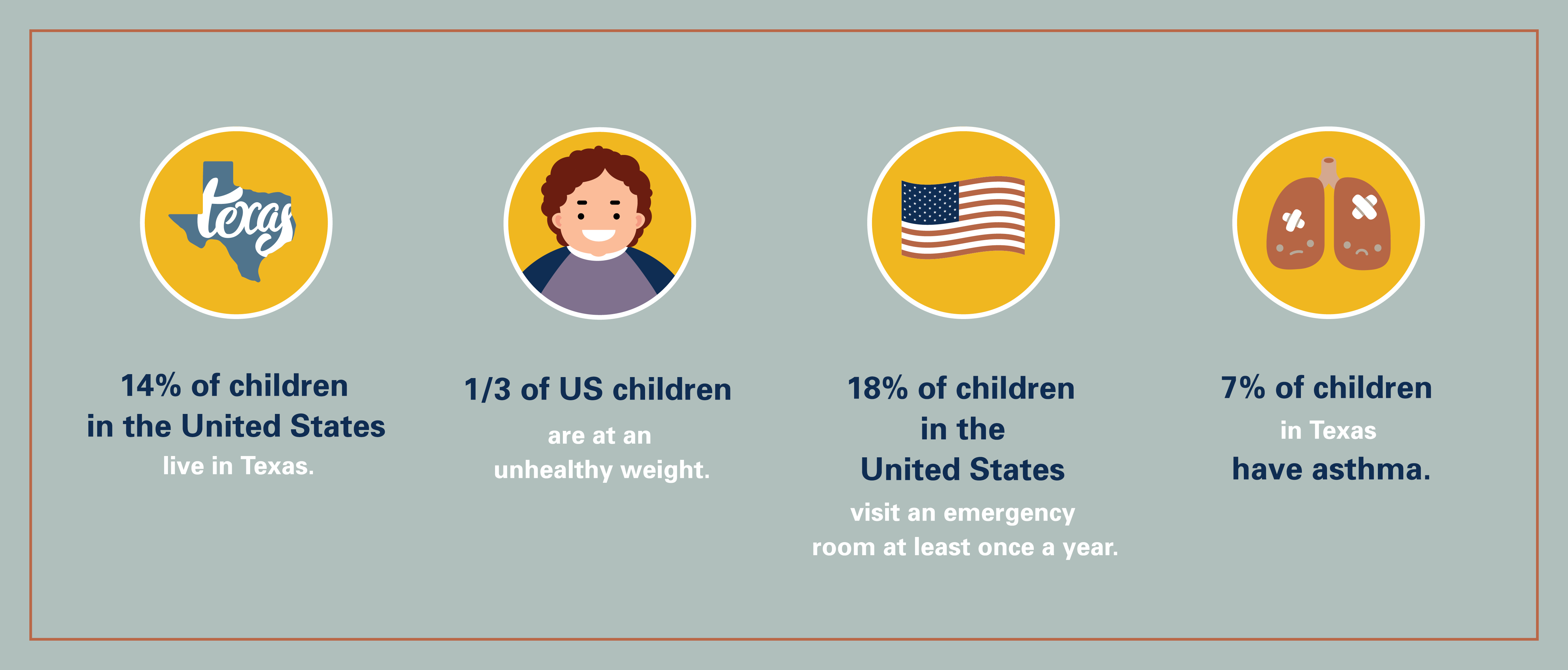

With about 7.4 million children, Texas has more than twice the number of Arkansas, Louisiana, Oklahoma, and New Mexico combined. While Texans may say everything here is bigger and better, children’s health is one area that could be improved.

“There is a lot of work to be done in the state, especially given that one in seven children in the United States lives in Texas, we need to refocus our attention on their health,” says Sarah Messiah, PhD, Director of a new center focused on improving wellness for children in North Texas. The Center for Pediatric Population Health is a collaboration between UTHealth School of Public Health in Dallas and Children’s Health.

The Dallas-based center supports the school’s statewide multidisciplinary research teams. Those researchers work with health care providers and community organizations to improve the physical and mental health of children and adolescents through prevention, better health outcomes after illness or injury, and effective use of health care services. The collaboration with Children’s Health, for example, focuses on improving wellness for North Texas children.

Research shows healthy children grow to become healthy adults, with population health serving as a bridge between traditional public health and health care services.

“Children’s Health and the School of Public Health have resources that can be incredibly powerful to address childhood health issues head-on,” says Messiah. “But we also need the research to determine if these approaches are best practices.”

Messiah says one of the first things she discovered when she moved to Dallas from Miami was the high incidents of asthma in children in the Dallas-Fort Worth Metropolitan Area: about 10% of all children and 12% of African-American children. As a result, these asthma patients were swamping local clinics. To address the issue, Children’s Health rolled out 150 digitally connected school clinics staffed by school nurses. Researchers at the Center for Pediatric Population Health analyzed patient data and found that asthma was the reason for more than half of the clinic visits.

“If we can control asthma in a school-based setting and make sure the kids are taking their medication, they won’t end up in the clinics and overburden the system with coughs and other related symptoms because the parents can’t afford the asthma medication,” Messiah says.

The center can also play a major role in healthy weight development by helping pediatricians connect families with school- or community-based physical activity programs, which researchers can evaluate to determine effectiveness. Exercise, however, is only part of the healthy equation, according to Messiah.

“Today’s children are the first generation whose parents grew up in the obesity epidemic. Parents are so challenged right now with their own health issues— pre-diabetes, cardiovascular disease—that it’s not just about nutrition and activities for one child, but for the whole family,” she says. “And when you consider that one out of three children and half of all minority children across the board are at an unhealthy weight, you’re playing catch-up all the time.”

Success is the measure of any plan, and that is true for Messiah and the center. She says decline in the number of asthma-related clinic visits would be one measure of success. Another would be fewer incidents among children of pre-diabetes, high blood pressure, and other metabolic factors leading to diabetes, stroke, and heart disease in adulthood.

Messiah also wants to help launch the careers of the center’s faculty and students so they can contribute to pediatric health in Texas and across the country. “I want to build a team of experts in various fields,” she says. Another goal is to build the center’s reputation as a place that provides world-class training in public health methodology that interfaces with clinical settings.

“There is no other center like this anywhere,” Messiah says. “We are at the intersection of public health and clinical care. To me, this is what pediatric population health is all about.”